Technical Content Planning System for Data Engineers Who Write

How to plan, schedule, and ship long-form writing using the same process you use for data work

In the previous piece, I explained why I plan content the same way I plan data work.

This one is different. This is about what I actually do. The tools I use. The order I use them in. The decisions I make once so I don’t have to remake them every week.

This is the operational loop I run to plan and ship long-form writing consistently, without turning every publishing day into a new problem.

If you already know how to plan data engineering work, this should feel familiar.

The Stack: The Only Three Tools That Matter

I don’t have a complicated setup. That’s intentional. The goal is to move decisions earlier and make execution boring. For that, I only need three tools.

First, a notebook.

This is an inbox. Ideas land here when they show up. A thought from work. A pattern from a conversation. Something that annoyed me enough to write it down.

Nothing gets prioritized here. Nothing gets scheduled here. This is raw intake only.

Second, AI.

Not for writing, but for opinions. I use it for expansion and extraction. It helps me widen the space when I’m planning and pull structure out of my own experience.

It never decides what matters. It just helps me see what’s already there faster.

Third, a calendar.

This is the only source of truth. If something is not on the calendar, it does not exist as work. Buckets don’t count. Lists don’t count. Good intentions definitely don’t count.

The calendar is where ideas either become commitments or stay ideas.

That’s the whole stack.

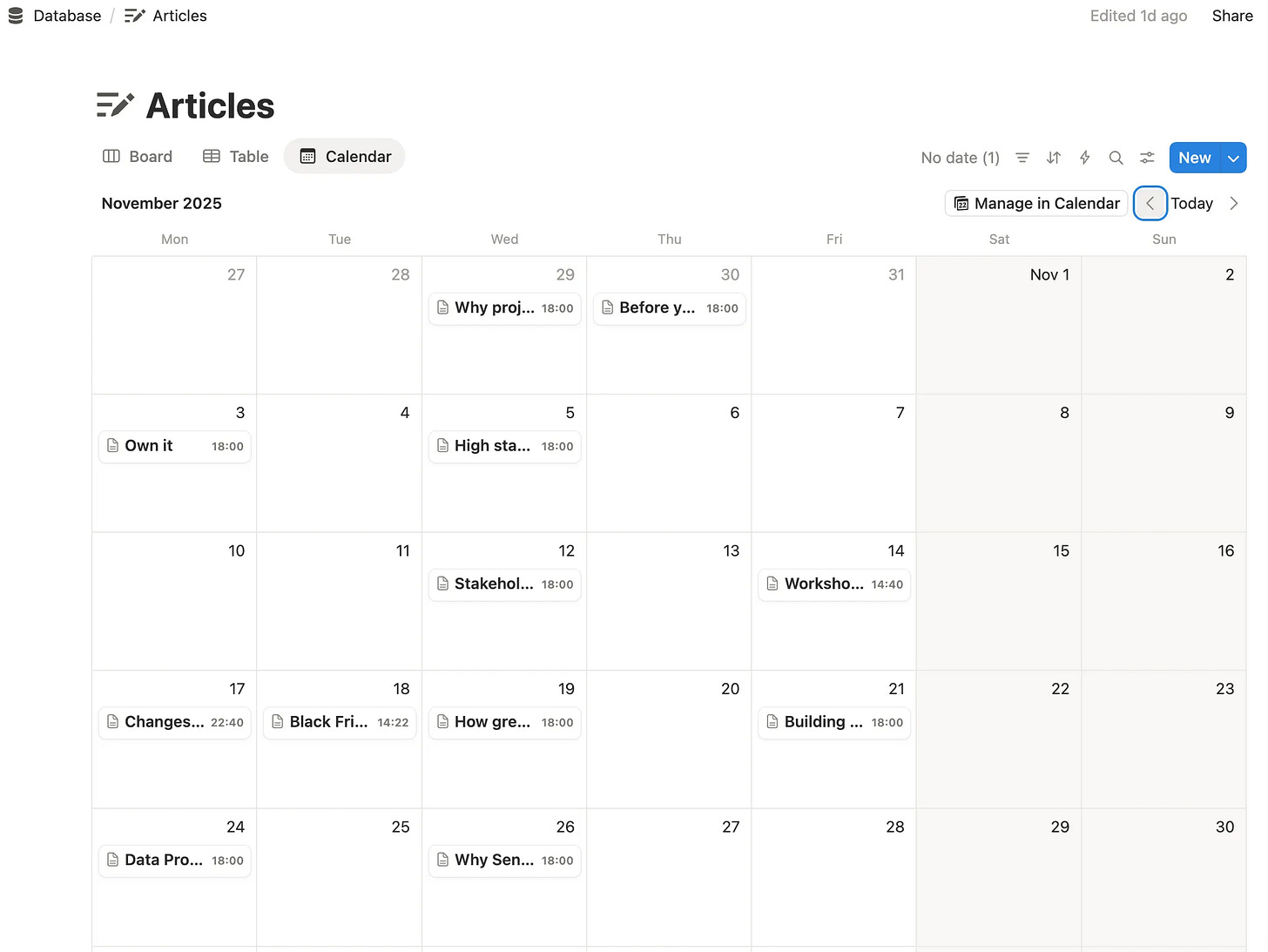

Planning Horizons: This Is Just a Data Roadmap

I don’t plan content continuously. I plan it the same way I plan data work: by locking decisions at the right altitude.

If everything is always up for debate, nothing ever ships. So I separate planning by horizon, exactly like I would for a data platform.

Yearly (November / December)

This is roadmap time.

I decide what content products exist, what problems they solve, and how often they ship. This is no different from defining platforms, domains, or major initiatives for the year.

By the end of this phase, the calendar already contains the releases with actual ship dates.

In data terms, this is where the architecture is chosen. You don’t redesign it every sprint.

Quarterly

This is portfolio review.

I look at what created signal, what didn’t, and what earned continued investment. Some products get killed. Some get more capacity. Some get deprioritized.

I’m not inventing new platforms here. I’m managing risk and return.

In your data job, this is where you decide which pipelines stay, which get refactored, and which should have been deleted six months ago.

Monthly

This is iteration.

I refine upcoming pieces, adjust sequencing, and tighten scope. The structure stays the same. The execution gets better.

This is sprint-level planning. You improve how you deliver against the roadmap.

Weekly

This is execution.

I open the calendar and build what’s scheduled. No re-architecture. No reprioritization. No existential questions.

In your 9-5, this is on-call plus delivery. You don’t redesign the warehouse because you’re tired on Tuesday.

If I feel the urge to “rethink the plan” during the week, that’s not intuition. That’s a planning failure upstream.

Weekly time is for shipping. All real thinking happens earlier, when the cost of changing your mind is low.

From Idea Inbox to Content Product

This is where most people confuse activity with progress.

Ideas show up constantly. From work. From conversations. From frustration. That part is normal. What matters is where those ideas go and what you do with them.

Every idea goes into a notebook.

That notebook is my intake system. The same way logs capture events without deciding what they mean yet. You can use, Apple notes or an Obsidian document.

During yearly planning, I review that notebook and apply a filter. Most ideas fail here, and that’s the point.

An idea is eligible to become a content product only if it meets all of these conditions:

I’ve lived it myself. Not read about it. Not inferred it.

It maps directly to the mission I already defined.

It’s something I’d be willing to revisit repeatedly over time.

If an idea doesn’t pass that filter, it stays parked. Storage is cheap, and attention isn’t.

This is exactly how mature data teams work.

You don’t turn every dataset into a pipeline. You don’t productionize every experiment. Most inputs are noise until proven otherwise.

A content product is a commitment. Once something crosses that line, it gets cadence, slots, and calendar time. Until then, it’s just raw signal sitting in an inbox, waiting to earn its place.

Read more about the cadence and content products in the previous piece.

The AI Loop: Expand, Prune, Extract, Schedule

This is where tooling actually matters.

I use AI during planning, not during writing. Its role is to accelerate structure, not produce content. The loop stays the same every time, which makes it reliable.

1. Expansion

I give AI the context of the product. The mission. The audience. The constraint created by cadence. Then I ask it to expand the space. Possible angles. Likely objections. Adjacent themes. Questions someone serious would ask.

This stage increases surface area. It helps me see the terrain faster than I would on my own.

I’m designing a long-form content product for experienced data engineers.

The goal of the product is: [insert goal].

The audience struggles with: [insert real problems you see at work].

The product will ship once a month.

List possible angles, objections, recurring questions, and adjacent themes this product could cover.2. Pruning

I review the expanded space and narrow it down to one direction. One promise. One line of thinking worth committing to for twelve releases. This is a judgment call. Experience matters here.

AI surfaces options. I choose the direction.

Based on everything above, help me pressure-test this direction:

[insert chosen focus].

What would make this weak, repetitive, or hard to sustain over twelve releases?3. Extraction

Once the direction is clear, I ask AI to interview me. Not to answer questions, but to ask them. The interview is structured around how I actually work. Decisions I’ve made. Tradeoffs I’ve seen. Mistakes that changed my approach.

I answer from memory and practice. This turns tacit knowledge into raw material.

Interview me about how I actually approach [insert topic].

Ask about decisions, tradeoffs, failures, and patterns from real work.

Don’t explain. Just ask.4. Structuring

The interview transcript becomes the input for structure. I work with AI to cluster ideas into principles, systems, and sequences. From there, I extract twelve concrete pieces that belong together and build on each other.

At the end of this loop, I have a complete arc. Twelve titles. One product. Clear progression.

Based on this interview, propose a 50 topics to write about. No clever titles. Just clear topics and areas.

Focus on systems, not standalone opinions.I go back-and-forth through the whole process. And come up with real topics and titles. For each topic, I also write what my idea really is and what’s the benefit for you, the reader.

In data terms, this is schema design after exploration.

You explore the data first. Then you decide what structure deserves to exist. Once the structure is in place, execution becomes predictable.

AI speeds up exploration and extraction. Direction, judgment, and final structure stay with me.

The Calendar Is the Execution Layer

Everything before this point is planning. This is where planning turns into work.

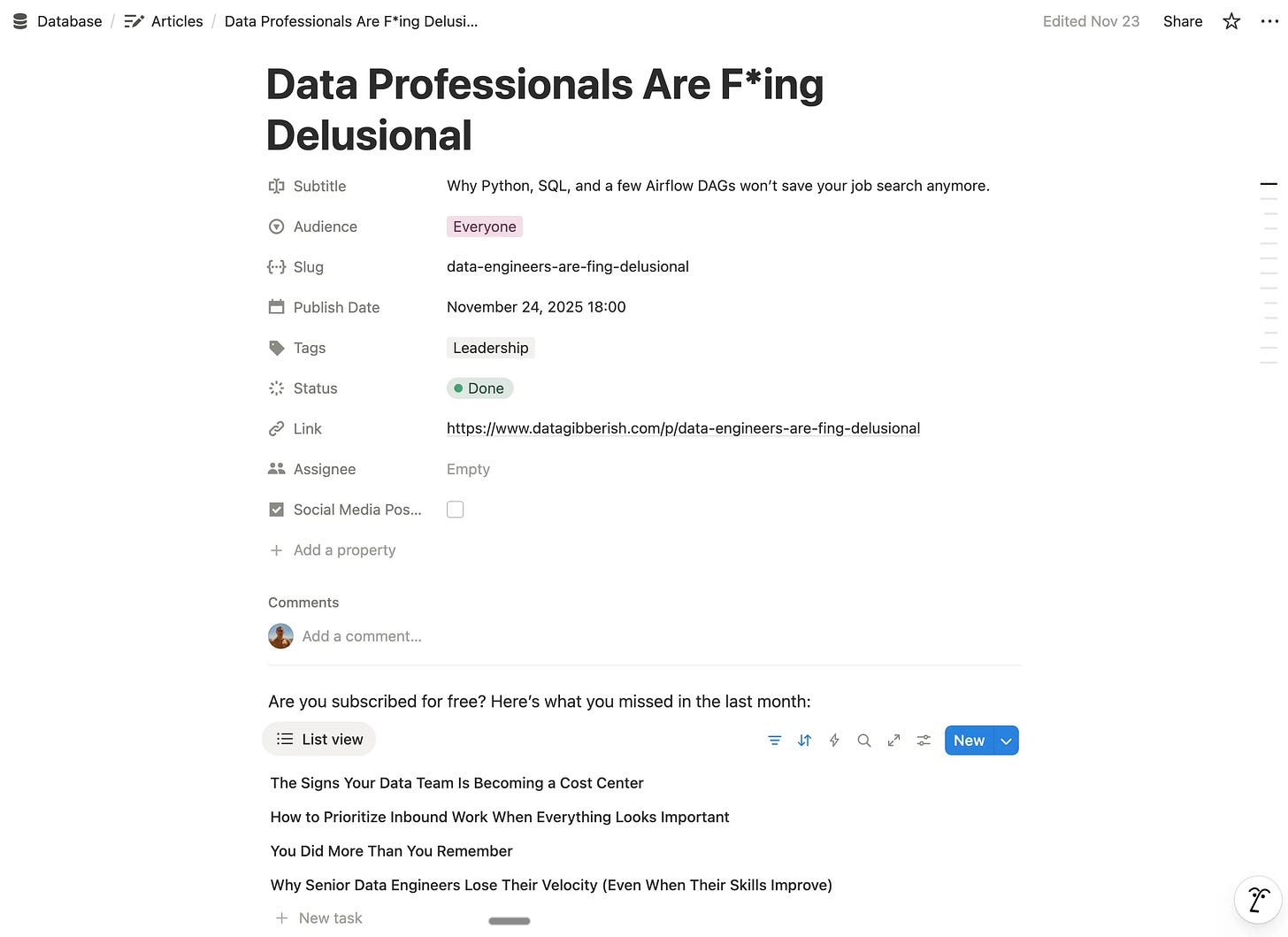

I use a calendar database on Notion as the execution layer because calendars force reality. Time is finite. Slots collide. Tradeoffs become visible without debate.

Once the calendar is populated, the system is effectively live.

Each entry on the calendar represents a release. Not an idea. Not a draft. A release. Every entry carries a small set of attributes so I can reason about the workload at a glance:

Ship date

Content product

Free or paid

Status

That’s enough structure to operate.

When I open the calendar, I can see capacity. I can see clustering. I can see whether I’ve overcommitted in a given week or left intentional space. This is the same reason data teams schedule jobs instead of relying on best effort execution.

In data terms, the calendar plays the role of an orchestrator.

Upstream planning defines what should run. The calendar defines when it runs. Once that contract exists, the daily question disappears. I don’t ask what to write. I look at what’s scheduled next.

This also changes how I relate to ideas.

Ideas don’t compete with scheduled work. They stay in the notebook until a slot opens. When a slot opens, I already know which product it belongs to and what kind of piece needs to ship.

Execution becomes predictable.

Writing stops being a creative negotiation and starts resembling delivery. The same way building a pipeline feels very different once it has a defined schedule and clear consumers.

At this stage, consistency is no longer a personality trait. It’s a property of the system.

A Quick Disclaimer About Systems

This is the system that works for me.

I plan writing the same way I plan data work because that’s how my brain operates. Structure gives me leverage. Predictability gives me space to think. I get better output when decisions are made early and execution is boring.

That doesn’t make this the correct approach. It makes it a compatible one.

I know excellent writers who actively dislike this style of planning. Some of them operate in what looks like chaos and still outperform most people. One of my friends thrives that way and consistently pulls in serious money writing without a rigid system. You can see an example here if you’re curious

The point is not to copy my setup line by line.

The point is to recognize the underlying question: what kind of system lets you show up consistently without fighting yourself?

For me, that answer looks like calendars, cadence, and upfront planning. For someone else, it might look like loose themes, bursts of output, and rapid pivots.

Stealing someone else’s system without understanding your own tendencies usually backfires. Borrow structure. Borrow ideas. Then adapt them until the system fits how you actually work.

The Tools I Use to Write

I keep the tooling simple and stable. Each tool has a clear role, and I avoid overlap as much as possible.

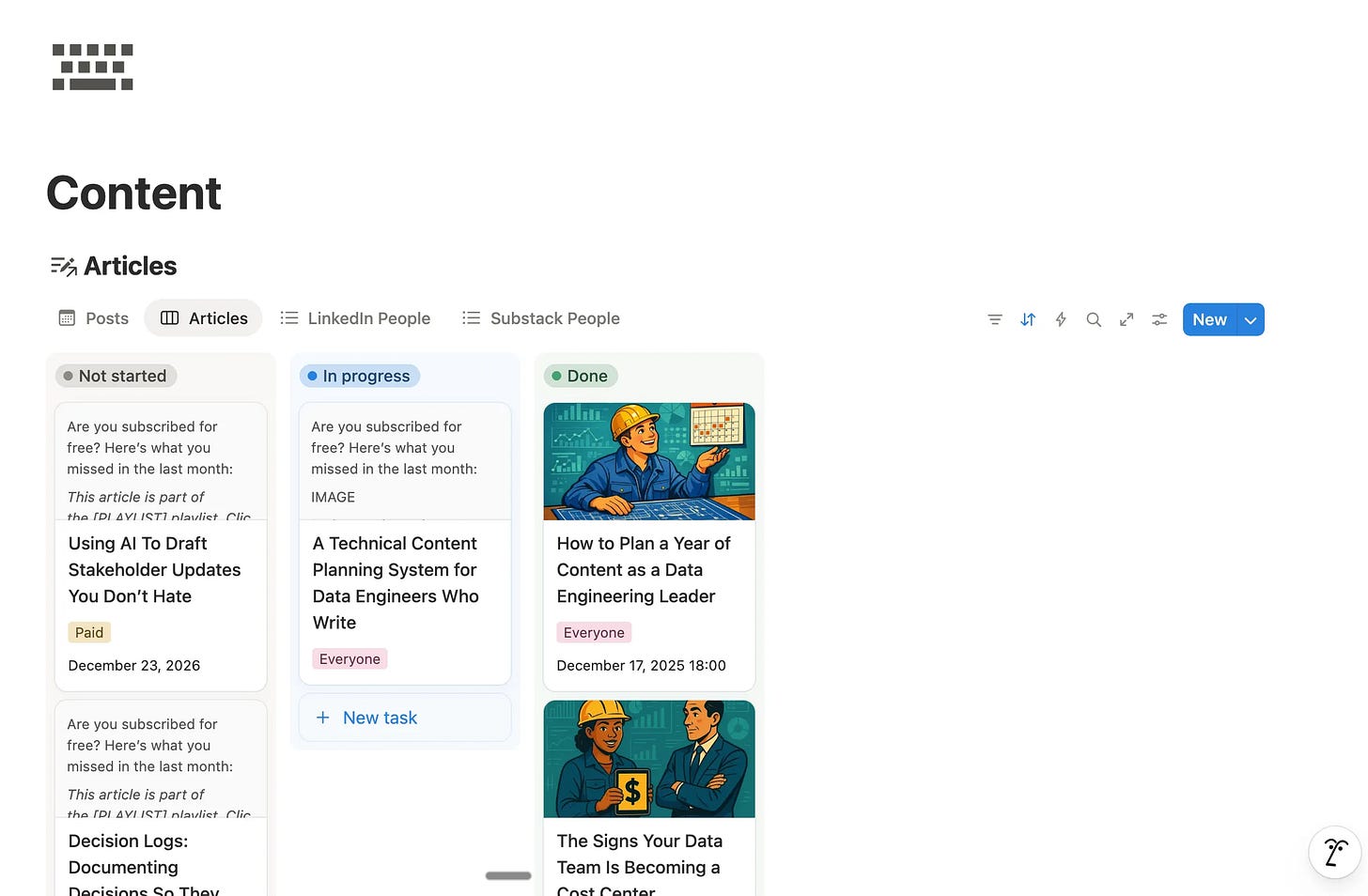

Notion

This is where planning lives. Calendars, product arcs, and high-level structure sit here. It’s the place where ideas turn into commitments. I use Notion for everything outside of writing too, and still haven’t paid a dime.

https://www.notion.com/product

ChatGPT

I use it for planning, interviewing, and structuring. It helps me expand the space and extract signal from my own experience. I don’t use it to invent systems or opinions.

Grammarly

This handles basic language cleanup. It catches things my eyes miss when I’m focused on structure and argument. I use it less and less, as it started feeling too robotic, but it really works well.

Wispr Flow

I use this for voice dictation when ideas come faster than typing. It’s especially useful for rough drafts and notes that don’t need polish yet. This single tool cut my writing time in half.

https://wisprflow.ai/r?YORDAN1 (affiliate link).

Bullet Journal

This is my idea inbox. Friction, observations, half-formed thoughts, and patterns from work land here first. Most of them never turn into articles, and that’s fine. As you can guess, I use this for much more that content.

Meld Studio

I use this to stream my live workshops here on Substack and record my The Data Leader’s Influence System course.

Canva

I use it for simple visuals and diagrams when text alone isn’t enough. I build slideshow using my own Canva template.

That’s the full stack.

I don’t chase tools. I keep the ones that reduce friction and drop the rest. The system matters more than the software, and the output matters more than both.

Final Thoughts

At some point, writing stops feeling like a separate activity.

It starts to resemble the rest of the work you already know how to do. You define outcomes early. You place decisions where they’re cheap. You let structure carry execution when energy drops.

That’s the real shift this system creates.

Consistency stops depending on motivation. Ideas stop competing for attention. Weekly output stops requiring fresh judgment. The system absorbs all of that.

For data engineers, this is familiar territory.

The same discipline that makes data platforms reliable also makes long-form writing sustainable. Once the planning work is done, writing becomes delivery. Predictable. Boring in the right way. Effective over time.

At that point, content compounds for the same reason good systems do. Because it’s built to run.

Thanks for reading,

Yordan

PS: Do you enjoy Data Gibberish? Post a public testimonial. It takes 30 seconds and helps fellow data professionals. Be a champion.