How to Plan a Year of Content as a Data Engineering Leader

How a systems-first planning mindset saves time, reduces decision fatigue, and keeps you writing long-term

Earlier this week, I asked my community in the Data Gibberish Substack chat what they want to learn in 2026.

Lavanya Mishra asked about my content planning process. And this is not a random question. Loads of data pros joined Substack recently. They have great ideas, but give up after a couple of articles.

The truth is that most people don’t fail at writing because they lack ideas. They fail because they decide in the moment. Every week becomes a fresh problem like: What should I write about? Is this good enough? Do I even have time?

In data engineering, we already know what happens when you don’t plan. Projects drag. Everything feels urgent. You spend more time thinking about what to do than actually doing it.

Writing works the same way.

This article is about how to plan a year of content using the same mindset you already use as a data engineering leader. Just a system that removes friction and saves time when it actually matters. This one is more about the philosophy, and next time I’ll tell you about the “tooling”.

I Plan Content the Same Way I Plan My Job

I start with the big thing.

What do I actually want to achieve next year? Not what do I want to write about, but what should change because this content exists.

Once that’s clear, everything else is just backtracing.

If this is the outcome, what is the one big step that gets me closer? And if that’s the step, what needs to happen before that? And before that?

You keep breaking it down until you reach something you can put on a calendar.

This is how most data engineers already think at work, right?

You don’t start with pipelines. You don’t start with tools. You start with a goal. A business outcome. A problem that needs to be solved. Then you design backwards until you end up with concrete tasks.

Writing works exactly the same way.

The biggest mistake I see is people trying to decide week by week what they feel like writing. That’s just unplanned work.

Planning upfront moves all the hard thinking into a dedicated block of time. Your brain switches into planning mode once, instead of doing it over and over again every week. The first decision is hard. The second is easier. The tenth feels obvious.

After that, writing stops being a decision-making exercise. It becomes execution.

Same reason data work feels lighter once the first version of a system exists. You’re not inventing from scratch anymore. You’re extending something you already designed.

Start With the Mission, Not Topics

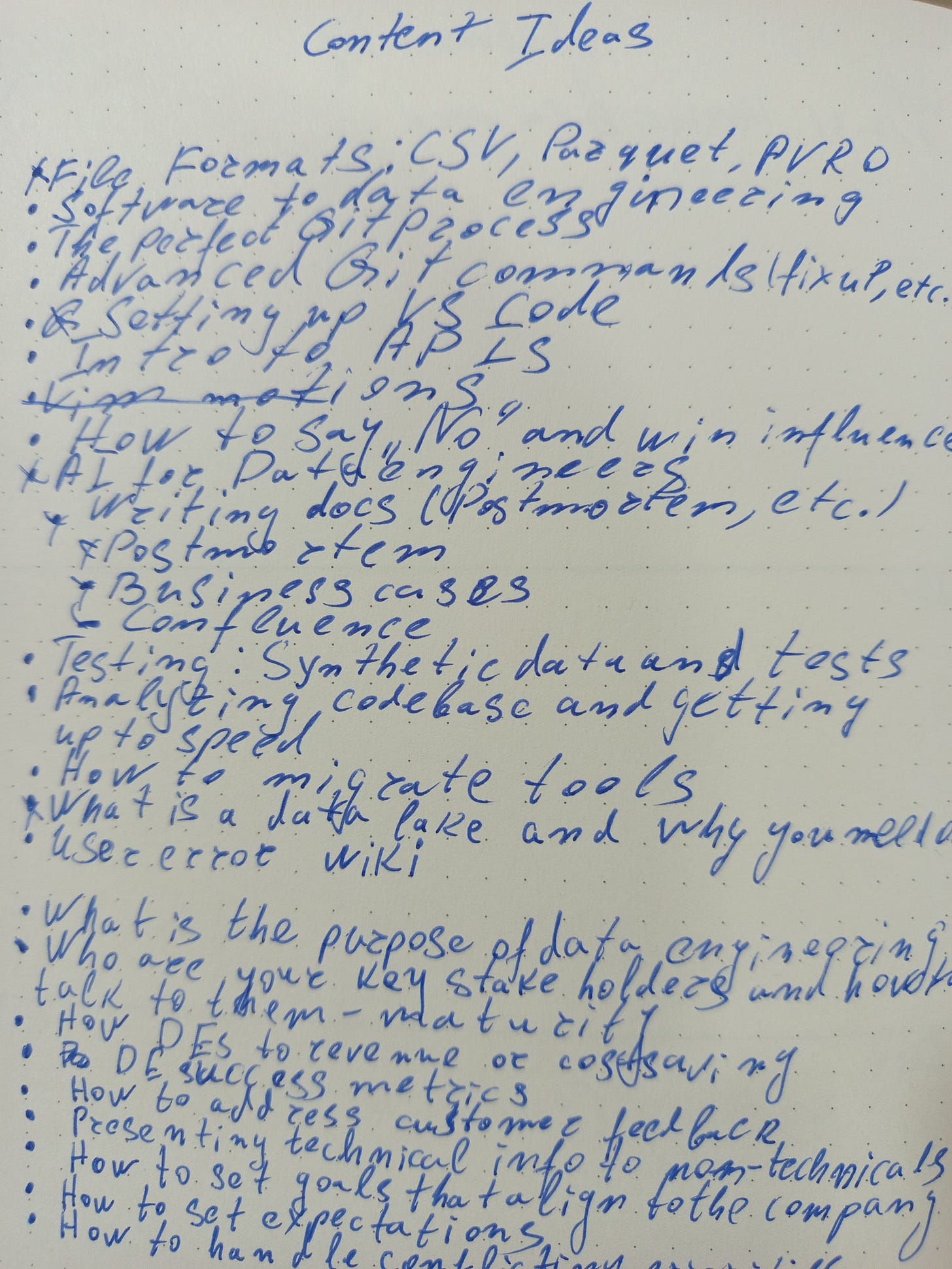

Most people start content planning by listing topics. That already puts them on the wrong path.

Topics are easy to generate. You can come up with fifty of them in five minutes. They feel productive, but they don’t tell you where you’re going or why any of it should exist.

I start with the mission.

For my publication, the mission is not to teach more tools. The internet doesn’t need another explanation of Kafka, Spark, or infrastructure patterns. There’s no shortage of that content.

My mission is different. It’s about helping technical people grow into bigger roles, bigger opportunities, and premium contracts.

From experience, I know that this doesn’t happen by going deeper into technical details alone. There are gaps in how technical people think about work, visibility, decision-making, and career progression, I don’t know about any other publication that does that in the data reality.

Once that mission is clear, a lot of ideas disqualify themselves automatically.

If a piece doesn’t serve that goal, it doesn’t belong in the plan. Even if it’s interesting. Even if it would be easy to write.

This is no different from data work.

You don’t build pipelines because they’re fun. You build them because they support a business outcome. If a solution doesn’t answer a real need, it’s noise.

The same filter applies to writing.

A clear mission reduces decision fatigue before it even shows up. It turns content planning from “what should I write about next?” into “what’s the next logical step toward this goal?”

Your Readers Are Stakeholders, Not an Abstract Audience

A lot of people plan content in isolation. They picture an audience in their head and start writing for them. I’ve done that too.

At work, you don’t design data solutions without talking to the people who will use them. You ask what they’re trying to do, where they’re stuck, what’s annoying them, and what success actually looks like.

Content works the same way.

The more I talk to readers, the clearer the gaps become. Not just what they say they want to learn, but what they struggle with day to day. Especially earlier in their careers, people often ask for one thing while needing something else entirely.

Those conversations shape the plan more than any brainstorm ever could.

I also talk to other writers and builders, not only in data but in completely different niches. When you do that, you start seeing patterns. You borrow ideas. You adapt things that work elsewhere. Then you combine them with your own background and experience.

That’s how you end up with something that doesn’t feel generic.

And again, this is normal data engineering thinking.

You don’t ship a generic solution just because it’s popular. You design something that fits your stakeholders, your constraints, and your environment.

Planning content is no different.

When you anchor your plan in real conversations instead of assumptions, you stop guessing. And once the guessing is gone, planning becomes much easier to sustain.

Stop Treating Your Newsletter Like a Personal Blog

Most newsletters fail because they’re treated like diaries.

People write when they feel like it. On whatever topic is top of mind. Sometimes twice in a week, sometimes nothing for a month. There’s no expectation on either side.

I started like that, too. That might be fine for a personal blog. It doesn’t work if you want people to take your writing seriously.

At some point, you have to commit.

For me, that meant choosing a cadence and sticking to it. Every Wednesday. Same time. No negotiation. Recently, I added Mondays as well, but the principle stayed the same.

Once you do that, something interesting happens. Your readers start expecting you. And you start planning differently because you’ve created a constraint.

This is exactly how data systems work.

You don’t run pipelines “when you feel like it”. You define when they start, when they finish, and when stakeholders can rely on the output. Predictability builds trust.

Treating a publication as a product instead of a blog forces the same mindset.

You stop asking, “Do I feel like writing this week?” You start asking, “What needs to ship on Wednesday?”

That shift alone removes a surprising amount of friction.

Think in Products, Not Posts

Once cadence is fixed, the next mistake is thinking in individual articles.

Single posts feel harmless, but they hide a problem. Each one is treated as a standalone decision. A standalone idea. A standalone effort. That’s how writing turns into noise.

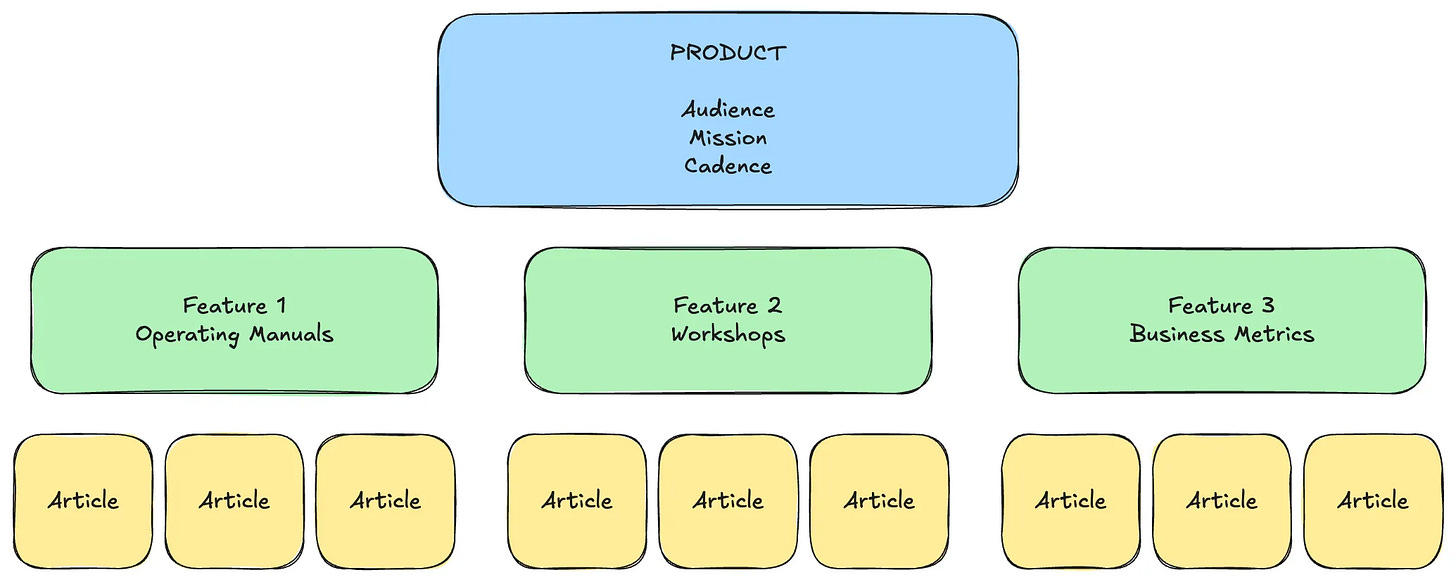

Instead, I treat the publication itself as a product. Not metaphorically. Literally. Like any product, it has a clear goal. And like any product, it has features.

The Wednesday pieces are work in progress features of the same system. Small Lego bricks that eventually form something bigger and usable. Each one exists because it moves the product closer to its goal.

That framing changes how planning works. I don’t ask, “What should I write this Wednesday?” I ask, “What feature needs to be built next?”

I plan those features plan upfront. Then build in public, one piece at a time.

This is familiar territory in data engineering.

You don’t ship a data product by randomly building pipelines. You define what the product should enable, break it down into capabilities, and then implement those capabilities incrementally. Each piece is small. The product is not.

When articles are treated as features, they gain direction. They stop being disposable. They start compounding. And planning stops feeling like guesswork.

Prototype First, Commit Later

Even with a clear goal and a product mindset, I don’t lock myself into ideas too early. I treat most new things the same way I’d treat a new data solution. I prototype first.

That means running small experiments in public. A few articles. A couple of workshops. Slight variations of the same idea. Then I watch what happens.

Do people reply? Do they DM me? Do they reference the idea weeks later? Do they ask for a follow-up or try to apply it to their own work?

I don’t get many public comments or likes. Most of the useful feedback happens privately. And I’m fine with that. Private messages usually mean the content landed close to something real.

If something works, I double down. If it doesn’t, I drop it. No drama. No sunk-cost attachment.

This is a hard habit for engineers to learn.

We’re trained to finish what we start. But good systems are built by iteration. Killing ideas early is not failure. It’s how you protect time and focus.

In online writing, you don’t keep a feature just because you committed to it in a planning doc. You keep it because it creates value. And the moment it stops doing that, you move on.

This mindset makes long-term planning possible. Because once you know you’re allowed to change course, committing to a plan stops feeling risky.

Once the System Exists, Planning Gets Easy

This is the part most people never reach. Not because it’s hard, but because they give up before the system exists.

Once you know the goal of the publication, the cadence, and the features you’re building, planning stops being abstract. It becomes mechanical.

You’re no longer staring at a blank page asking what to write. You’re filling slots in a structure you already designed.

Take the Wednesday pieces as an example.

If you know that one recurring feature ships once a month, that’s twelve pieces a year. Suddenly the scope is small enough to think about calmly.

And most of the time, those pieces don’t require research. They come directly from the work you already do. Conversations you already have. Decisions you already make. Mistakes you’ve already learned from. You’re not inventing expertise. You’re documenting experience.

This is exactly how mature data systems feel.

Once the platform exists, adding a new dataset or pipeline isn’t a big event. The hard thinking already happened. You’re operating within constraints that help you move faster, not slower.

Content works the same way.

The upfront planning takes time. It’s uncomfortable. The first pass is messy. But every iteration gets easier. Mentally, it’s a huge relief.

You stop carrying the question “what should I write next?” around in your head. The answer is already there. You just show up and build the next piece.

Yes, You Can Use AI (Just Don’t Let It Think for You)

This usually comes up sooner or later, so it’s worth addressing directly.

Yes, you can use AI.

It’s not cheating. It’s not lazy. It’s just another tool. I use it myself, but very deliberately.

AI is useful for expanding the space. Brainstorming. Listing variations. Surfacing adjacent ideas I might not have considered yet. It replaces some of the heavy lifting when I’m planning, especially early on.

What it doesn’t replace is thinking.

I don’t ask AI what I should believe. I don’t ask it to invent opinions. And I don’t let it decide what belongs in the plan. That part still comes from experience and judgment.

I ask AI to interview me on the topic. Not to give me answers, but to surface questions I haven’t considered yet. That forces me to articulate what I actually think and why. From there, I use it to research adjacent ideas and angles, expand the space, and pressure-test my own assumptions. The final choices are still mine. AI just helps me see the terrain faster.

It’s not giving me ideas. It’s helping me notice the ones I already had. That makes planning faster, not shallower.

This is familiar in data engineering too.

Automation is great when it removes manual effort. It’s dangerous when it replaces understanding. You still need to know why a pipeline exists, what assumptions it makes, and when it breaks.

So, in writing, use AI to accelerate planning, not to outsource taste or responsibility. When you keep that boundary clear, it becomes a genuine advantage instead of a crutch.

Leave Leeway on Purpose

Even with a solid plan, I never plan everything and that’s intentional.

A plan that leaves no room to move will break the moment reality shows up. And reality always shows up. Just like this article!

Sometimes there’s a big piece of news. Sometimes a conversation hits a nerve. Sometimes an idea keeps coming back until you can’t ignore it. If the plan is too rigid, you either suppress those ideas or blow up the whole system to make space for them.

I treat the yearly plan as a guide, not a prison. Most of the structure is fixed, but some slots are deliberately open. That way, when something genuinely important appears, I can respond without guilt or chaos.

This is normal in data work.

You might plan major migrations, platform improvements, or long-term initiatives. But you never assume nothing unexpected will happen. Stakeholders bring new requests. Priorities shift. Sometimes the business changes direction overnight.

Good plans account for that. The same applies to content.

Planning doesn’t mean predicting the future perfectly. It means creating enough structure that change is manageable. When slack is built in, adapting doesn’t feel like failure. It feels like part of the system working as intended.

Reading and Writing Are a Flywheel

Ideas don’t come out of nowhere.

If you’re not reading, thinking, or writing regularly, planning a year of content will feel artificial. Like you’re forcing output without having anything to draw from.

What I’ve learned over time is that writing is not just a way to publish ideas. It’s a way to form them.

I talked about this on Joe Reis’s podcast recently (watch here). Writing forces clarity. You can’t hide behind vague thoughts once you try to put them into words. And once you do that often enough, something fascinating happens.

The more you write, the more you think. The more you think, the more you notice ideas worth writing about. It turns into a flywheel.

That’s why I write even when it’s not for publication. I keep a notebook next to me. I journal. I jot down half-formed ideas, frustrations, patterns I notice at work. Most of those notes never turn into articles. Some of them become the backbone of entire features months later.

This also explains why the yearly plan is not a rigid roadmap.

The plan gives direction. The daily writing keeps the system alive. Sometimes an idea shows up uninvited and demands attention. When that happens, I take the plan as a reference point, not a rulebook.

From a planning perspective, this matters.

You’re not trying to predict every idea you’ll have in the next twelve months. You’re creating a structure that can absorb new ones without falling apart. Reading and writing regularly is what feeds that structure.

Without that habit, planning becomes sterile. With it, the plan stays grounded in real thinking instead of forced output.

Final Thoughts

For me, writing is not a side hobby. It’s work. Not in the corporate sense. In the sense that it deserves the same respect, structure, and intentionality as the rest of my job.

The closer writing gets to how I already work as a data engineering leader, the easier it becomes to sustain. Planning upfront removes friction later. Decisions get made once, in a focused block of time, instead of being renegotiated every week when energy is low.

That’s the real payoff of planning a year of content.

You’re not trying to predict the future or lock yourself into a rigid roadmap. You’re building a system that carries you forward when motivation fades and attention shifts.

If you already know how to plan data work, you already know how to do this. You just need to apply the same discipline to writing.

Treat your content like a product. Build features deliberately. Leave room for change. And trust the system to do its job.

That’s how writing stops feeling heavy and starts compounding.

And that’s the “philosophical” part about my system. Next week, I’ll tell you more about the “technical” side with tools and stuff.

Thanks for reading,

Yordan

PS: Shout out to some of the folks in my network: Michał Poczwardowski, Erfan Hesami, Prajakta, Filipe Balseiro, Daniel Beach, Adrian Stanek, and everybody in the amazing Write • Build • Scale community. I’d never be so consistent without your support. ❤️

Now that's one awesome piece! Appreciate your shout-out, and I am grateful to be connected with you and learning from you. Keep pushing!

Awesome article Yordan! Thanks for writing about it! Looking forward to the tooling one!