Entropy Is The Default In Data

If your platform assumes order, predictability, or a known future, it will break the moment the business moves

The most common sound in a data team’s Slack channel is the collective sigh of a developer who just realized their last month of work is now officially legacy code before it even hit production.

You spent five weeks perfectly modeling a subscription attribution engine, handling every edge case, and making sure the DAGs were as clean as a whistle. Then, on Friday afternoon, the VP of Growth mentions that the company is moving away from subscriptions to a usage-based model.

The immediate reaction is to blame the business. You call them “fickle“ or “unorganized“. You moan about a lack of clear requirements and the absence of a roadmap. But that frustration comes from a place of architectural ego. You get attached to the “perfect“ solution you built in your heads, and when the reality of a living, breathing business crashes into that solution, you treat it like an insult.

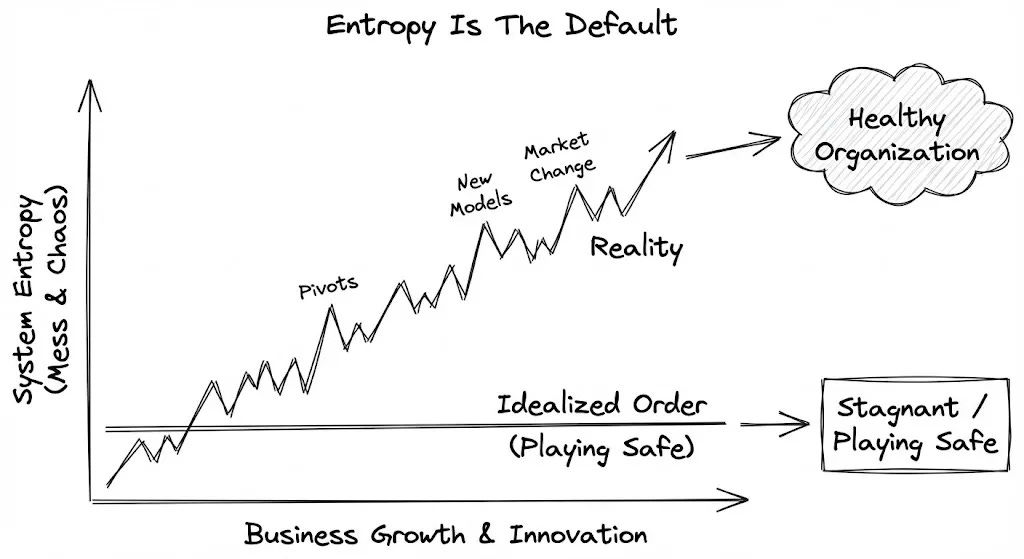

The truth is that if your organization doesn’t feel chaotic, it isn’t moving fast enough to survive.

Chaos is the sound of innovation.

If the requirements stayed the same for six months, it would mean nobody is learning anything about the market.

As data professionals, you and I are the translators of that chaos. Our job isn’t to build a static monument to a business model that existed in January. Our job is to build the pipes that can be rerouted the moment the floor plan changes.

When you spend five weeks building something “just in case“ or trying to “do it right“ by over-engineering for a future that hasn’t happened yet, you aren’t being a good engineer. You’re betting that you can predict the future better than the people actually running the business. And in data, the house always wins.

The Ego Tax

The reason you spend five weeks in a dark room building a monolithic masterpiece instead of shipping a “good enough“ pipeline in three days is simple: you are paying an ego tax.

You have been told your entire career that a “good“ engineer builds for scale, that they abstract everything into oblivion, and that they follow every “best practice“ found in a dusty textbook. You want your codebase to look like a cathedral, a stone monument of perfectly nested functions and rigid schemas that proves to anyone looking at your GitHub that you are a serious professional.

But the business you work for isn’t a quiet village looking for a cathedral. It is a dense, aggressive jungle that is trying to grow faster than the ground can support it.

When you build a stone fortress in a jungle, you are creating a future ruin. The moment the jungle shifts or a new path is cleared, your stone walls become a literal wall that the business has to climb over or demolish to keep moving. You get protective of your “clean“ code because you’ve tied your identity to the architecture.

But the business doesn’t care about your abstractions. It cares about whether it can see its revenue figures before the board meeting on Tuesday.

This architectural arrogance is a mask for insecurity. You are afraid that if you ship a simple script or a modular “campsite“ that can be packed up and moved tomorrow, people will think you don’t know how to build the complex stuff.

So you add layers of “just in case“ logic and generic wrappers that try to account for every possible pivot the business might make in the next three years. You call this “future-proofing“, but in reality, you are building a very expensive anchor. You are making the system so heavy that nobody, including you, will have the energy to change it when the assumptions you made five weeks ago inevitably turn out to be wrong.

The tax you pay for this ego is your own sanity. When that pivot happens, and you’re forced to tear down your cathedral, you feel like a failure. You feel like the business is “stupid“ for not appreciating your craft.

But the craft of a data engineer isn’t building things that last forever. It’s building things that are easy to change. You need to stop trying to be a stonemason and start being a scout. A scout builds a campsite with a fire and a tent because they know they’ll be miles away by morning. They don’t get attached to the dirt they’re standing on.

System Design for the Cynic

If you accept that entropy is the default, you stop designing systems that try to “solve“ the business. Instead, you design systems that survive it. This requires a level of healthy cynicism toward your own stack. You have to assume that every tool you use, every vendor you pay, and every model you write will eventually be the wrong choice.

The biggest mistake you make is letting your business logic get swallowed by your infrastructure. If your transformations only work because of a specific, proprietary feature of your cloud warehouse, you aren’t an engineer but a hostage.

To build a campsite, you keep your logic in a format that can move. This means writing modular, standard SQL or Python that lives in version control, not in a vendor’s UI. It means using a semantic layer so that when the business changes its mind about what “Gross Margin“ means, you change it in one file, not across forty-five different dashboards.

You also need to embrace the Primitive. A primitive is a basic building block, a single-purpose script, a discrete dbt model, or a standalone connector. When you build a “platform“, you are building a rigid structure that forces everyone to work a certain way. When you build a library of primitives, you give yourself the power to swap.

If a new ingestion tool comes out that is ten times cheaper than what you use today, a modular system allows you to unplug the old one and plug in the new one in an afternoon. If you’ve built a monolithic “Data Platform” that has its tentacles in every part of your workflow, that swap will take you six months and a dozen architecture review meetings.

Finally, you must practice Late-Binding Logic. The closer to the raw source you try to “fix“ the data, the more fragile your system becomes. If you try to force a strict schema on the data the moment it hits your environment, you are betting that the schema won’t change. You will lose that bet.

Keep the data as raw as possible for as long as possible. Only apply the “order“ at the very last second before the user sees it. This feels “messy“ to the part of your brain that wants a clean warehouse, but it is the only way to ensure that when the business pivots, you don’t have to re-run three years of historical data just to fix a renamed column.

The Process of “Not Knowing”

There is a fine line between being flexible and being a doormat. If you start a project without a frozen spec, you aren’t “being water“, but accruing Presumption Debt. You are making guesses about business logic that you cannot defend, and you will eventually have to pay that debt back with interest during a weekend of broken DAGs.

As I’ve written before, you need a Project Entry Manual. You need a scoping document that freezes intent and a public sign-off that turns a vague request into a concrete commitment. But here is where the “Be Water“ philosophy from Bruce Lee actually applies: The spec is the cup, not the water.

“Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water.”

In data engineering, your job is to be the water, and the Scoping Doc is the container the business has given you for this specific stage. You need that container to know where to flow. Without it, you’re just a puddle on the floor, useless and messy. But the “Be Water” mindset means you don’t fall in love with the container. You know that today the business needs a “Subscription Attribution“ cup, but tomorrow they might hand you a “Usage-Based“ bottle.

If you build your code as a rigid, stone monument to that first cup, you will break when the business tries to pour you into the bottle. You’ll point at your Scoping Doc and complain that the “requirements changed“, as if the business is a static thing that should stop moving for your convenience.

Instead, you use your Project Entry to freeze the intent for now so you don’t build on assumptions. But you use modular system design to ensure that when that intent inevitably expires, you can shift shapes without tearing down the entire infrastructure. You ship in stages, providing incremental exposure to the data, so that the feedback loop happens while you’re still in your “campsite“ phase.

Being water means you have the discipline to demand a clear requirement before you write a single line of SQL (to avoid Presumption Debt), but you have the humility to build that SQL so it can be deleted or refactored the moment the container changes. You demand the “cup“ so you can do your job, but you stay fluid so the “cup“ doesn’t become your cage.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve been reading this and nodding along, you probably have a half-finished “cathedral“ sitting in your repository right now. You have code that you’re proud of, but deep down, you know it’s too heavy to survive a change in the wind.

It is time to kill the “Data Architect“ in your head, the one that wants to build monuments, and start listening to the “Data Scout“.

Stop viewing the chaos of your organization as a failure of leadership. If the business wasn’t messy, it wouldn’t need you. A perfectly predictable business can be automated by a script written ten years ago. You are hired to navigate the entropy. You are paid to bridge the gap between a shifting business reality and a functioning data system.

When you insist on a scoping doc, you aren’t being a bureaucrat, but a professional who refuses to build on sand. But when you build that project using modular primitives and late-binding logic, you are being a realist who knows that today’s “frozen spec“ is tomorrow’s legacy debt.

The goal isn’t to reach a state where the data is “clean“ and the requirements never change. That state doesn’t exist. The goal is to reach a state of Zen with the Mess. It’s the feeling of knowing that when the CEO pivots the company on a Tuesday afternoon, you won’t have to spend your weekend rewriting three thousand lines of hard-coded logic. You’ll just adjust your primitives, pour the water into the new cup, and go home on time.

Build for the mess. Ride the entropy. Be water, my friend.

Thanks for reading,

Yordan

PS: Next time you call a stakeholder “stupid” for changing their mind, ask yourself if your architecture was actually built to handle the truth of a growing business.

PPS: I just vibecoded my personal website. You can check the complete write-up here.

Hi Yordan,

yep, the environment that businesses live in change and the business has to respond. Also the business can take initiative given their insight to the environment. This is why I have promoted the idea that the best way for businesses to respond to that change is to have as much data as possible available to the 5 smartest business people in the company so they can rummage through it testing their ideas.

My customers have made a LOT more money doing exactly that. If you have ALL the data in your data warehouse then when someone comes up with a new idea you have a pretty good chance of testing it.

Anything that is "rigid" is old before it arrives.